Introduction and Justification

Safety dominates the self-driving car discussion, representing the area of both greatest benefit and greatest concern. Proponents of the technology expound the virtues of the autonomous vehicle (AV).

The key talking points are compelling: an ever-vigilant machine that reacts at the speed of thought makes humans seem like apes behind the wheel. For detractors, safety is the area of greatest concern.

Deep learning models like Convoluted Neural Networks (CNNs) are particularly effective at image processing and environment modelling (Barla, 2023) that make self-driving cars possible, but they are still brittle in novel situations and how they “think” is opaque.

Recent advances in neural network mapping may give more insight into AI decision-making in future, but this is still far removed from the level of control we are accustomed to having over classical safety-critical automated systems.

SAE Five Levels of Automation

The Society of Automated Vehicles International has defined five levels of automation, with a sixth level, ‘Zero’, for unautomated vehicles. Levels 0 through 2 are categorised by features that support the driver, such as adaptive cruise control and lane departure warning.

Even if the vehicle is controlling the acceleration, breaking, or steering, this classification considers that the human driver is still driving the vehicle (SAE International, 2021).

The classification considers the remaining three levels to be automated, and that a human in the driver’s seat is not driving whilst these features are active.

At Level 3, the vehicle can drive itself, but the human driver must take over when prompted to do so. Whilst SAE International (2021) characterises this as a peer of the more automated Levels 4 and 5, colloquially, vehicles with these features are rarely considered to be ‘self-driving’ cars.

At Levels 4 and 5, vehicles can complete a trip without any driver input and are typically considered to be ‘self-driving’. Fifth Level vehicles can drive themselves regardless of limitations that may be imposed on Fourth Level vehicles such as geo-fencing, poor visibility etc. Fifth Level may be considered the ultimate goal of self-driving vehicle development (SAE International, 2021).

How They Work

The modern road environment is unpredictable, and interpreting it correctly is fundamental. To this end, AVs are equipped with RADAR (Radio Detection and Ranging) and LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) to map the depth of the local environment (Paden et al., 2016).

Camera arrays provide a finer picture of the near environment and use parallax to judge distance, which can be corroborated with range-finding sensors and ultrasonic sensors for judging the distance to extremely close obstacles, such as other cars and curbs. Inertial measurement units (IMUs), odometers and GPS can judge the motion, pitch, yaw and roll of the vehicle in space independently.

If other more precise but more fragile sensors are rendered inoperative, the inertial sensors can function as a failsafe to bring the vehicle to a safe halt. This data is processed in real-time by the operating system (OS) to create a map of both the static environment and dynamic objects within the environment. This map, or state, is combined with the vehicle’s state, and passed to the decision-making stack.

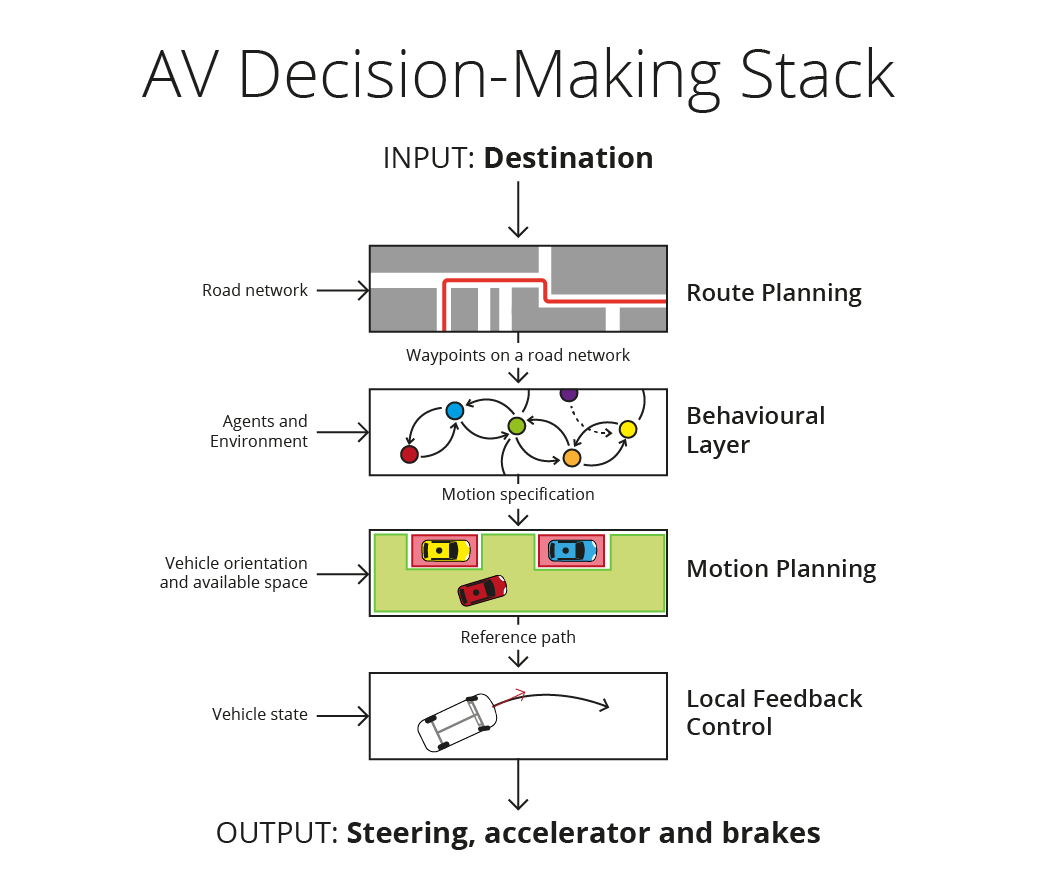

The first stage of this stack is route planning: the vehicle generates waypoints to its destination based on the known road layout and any perceived changes. This is then passed to a behavioural layer which “reasons about the environment and generates a motion specification to progress along the selected route.” (Paden et al., 2016)

Using the motion specification and data about the vehicle’s orientation and local space, the motion layer then plans the vehicle’s manoeuvre as a path vector. Finally, the path vector and the vehicle’s current state are used by the local feedback control layer to generate individual inputs to the vehicle itself.

Figure 1. Autonomous Vehicle Decision-Making Stack (Matthew Stockdale, 2023)

All four of these layers can be implemented using classical computer science solutions, such as A* for route planning, and a Finite State Machine or Markov Decision Processes for behaviour (Paden et al., 2016).

However, deep learning techniques such as Convoluted Neural Networks (CNNs) are particularly well-suited to some tasks such as image recognition and modelling spatial information. Deep learning techniques are particularly useful due to how quickly they can be trained and adjusted if relevant data is available, but some argue that they are brittle, and that not understanding how they work is inherently risky (Barla, 2023).

Classical approaches can be much more readily debugged, and their decision making can be understood by reading the code, which some consider critical for systems in which the safety of humans is involved.

Current Status

Since the public unveiling of the Google Self-Driving Car Project in 2010, now Waymo, investment has been thick and fast. Now, after over a decade of delays and setbacks, self-driving technology is no longer on the horizon: the push for integration is happening now.

In August 2022, the British government unveiled their plan for a wider rollout of self-driving vehicles by 2025, backed by a £100 million investment “to support industry investment and fund research on safety developments.” (Kwarteng & Shapps, 2022)

Waymo is currently operating its ride-hailing service in Phoenix and San Francisco, with plans to move into Los Angeles. Cruise, under GM (General Motors), also offers ride-hailing in Phoenix and San Francisco. Baidu offers its ‘robotaxis’ in several cities including Beijing and plans to expand to an ambitious 100 cities by 2030.

For all three companies, safety is a key part of their branding.

New Zealand currently has such no roadmap, despite having both high car ownership and high car dependency. In the absence of government programs, usual factors such as physical isolation and a small market meant AV manufacturers had no incentive to even consider the country as a candidate testbed.

However, the MOT issued a report in 2022 outlining possible impacts, as well as paths forward, and the NZTA is open to working with manufacturers interested in testing their vehicles in New Zealand.