Risk and Challenges

Transition Period

The transitory period when self-driving cars are first unleashed on public roads marks one of the greatest potential risk periods. At this time, self-driving cars will be working from relatively small datasets of ‘real-world’ scenarios (Dickson, 2020) and no amount of public messaging is going to ensure that every ‘Joe Public’ is going to respond to these new cars in a sensible manner.

“It takes a long time to turn over the U.S. fleet of light-duty vehicles, with the average vehicular age currently being 11.4 years.” Therefore, “there will likely be at least a several-decade-long period during which conventional and self-driving vehicles would need to interact.” (Sivak & Schoettle, 2015)

During this transition period, it is important to acknowledge the risks of the coexistence between self-driving cars and conventional vehicles, as safety may worsen. Sivak and Schoettle (2015) state “in many current situations, interacting drivers of conventional vehicles make eye contact and proceed according to the feedback received from other drivers. Such feedback would be absent in interactions with self-driving vehicles.”

Dickson (2020) argues that we will not get Level 5 vehicles via deep learning as they must deal with human drivers still on the road, though he fails to consider that the transition period will not last forever. He primarily considers Tesla as an example for self-driving vehicles, failing to account for the other companies who are working on self-driving technology.

Furthermore, Dickson takes the viewpoint that deep learning is not akin to the human mind, instead being “fundamentally flawed because it can only interpolate.”

Though this may indeed be the case, and would support Sivak and Schoettle’s absent feedback argument, the opaque nature of deep learning models cannot currently prove Dickson and those who agree with him correct.

Deep Learning Models are Opaque in Their Decision-making

Deep learning models, like those used in AI, are inherently opaque. Engineers may understand what the car sensed and how the car responded to a situation, but in many implementations, crucial aspects of decision-making seem to occur in a ‘black box’. (Stilgoe, 2021).

This is in sharp contrast to the state-based and deterministic automated systems to which we are accustomed. When these types of systems fail a decision-making process, the failure can be identified, fixed, and tested with a high degree of confidence. When a deep learning model fails, this is usually indicative of an alignment issue.

Alignment issues typically arise when the deep learning model learns incorrectly, such as learning the wrong goal, and thus arrives at the incorrect outcome. This is known as an “out-of-distribution generalisation” failure, where a deep learning model should perform “well on test data that is not distributed identically to the training set”, yet fails (Langosco et al., 2023).

This type of alignment issue “is a fundamental problem in machine learning” (Langosco et al., 2023) as it cannot be reasonably assumed that the model can distinguish between its “terminal goal” and its “instrumental goal” (Miles, 2021). An out-of-distribution failure could therefore cause safety issues - or even something as simple as making passengers late - with self-driving cars.

It is worth noting that whilst deep learning decision-making isn’t entirely opaque, as their learning processes can be observed, there is a lack of understanding on why they come to certain conclusions about their objectives based on their teachings, thus potentially making them dangerous.

Ethical Dilemmas & the Trolley Problem

Addressing the problem of AI ethics will be critical for public acceptance of self-driving cars, and failure to properly align AI decision-making may have serious long-term consequences for the self-driving industry.

The question of ethics is cast into its sharpest relief when introducing vehicle AI to dilemmas: scenarios in which, no matter which course the car takes, some harm is inevitable. This represents a new frontier for humanity, as never before have we tasked machines with valuing human life to this degree.

The MIT launched ‘the Moral Machine experiment’ in June 2016 with the goal of starting discussion and providing moral guidance to self-driving vehicle designers. Survey participants were provided with a birds-eye view of an ethical dilemma and tasked with picking a preferred outcome.

The findings demonstrated a strong preference for sparing human lives over those of pets, sparing more people over fewer, sparing the young, and sparing those lawful and of higher status, such as doctors and pregnant women. (Furey & Hill, 2021)

These preferences, however, vary significantly by region. For example, countries in the ‘Eastern’ region (broadly speaking, every Eurasian country between Iran and Japan) having a preference towards the elderly. The broad array of correlations between distinct cultures suggests that the question of the machine ethics may not have a one-size-fits-all solution, despite much talk of the need for AI to reflect human values.

Furey and Hill (2020) argue that the focus on ‘trolley problem’-style dilemmas may cause more harm than good. Specifically, that by focusing on accidents that represent edge cases, the adoption of AVs may have been slowed, preventing them from saving lives attributed to one of the primary causes of road accidents: human driver error. Furthermore, Furey and Hill (2020) argue it may place unnecessary moral discomfort on the public: “[The Moral Machine] has caused the public to think they must choose between purchasing an autonomous vehicle that protects their family and one that is moral.”

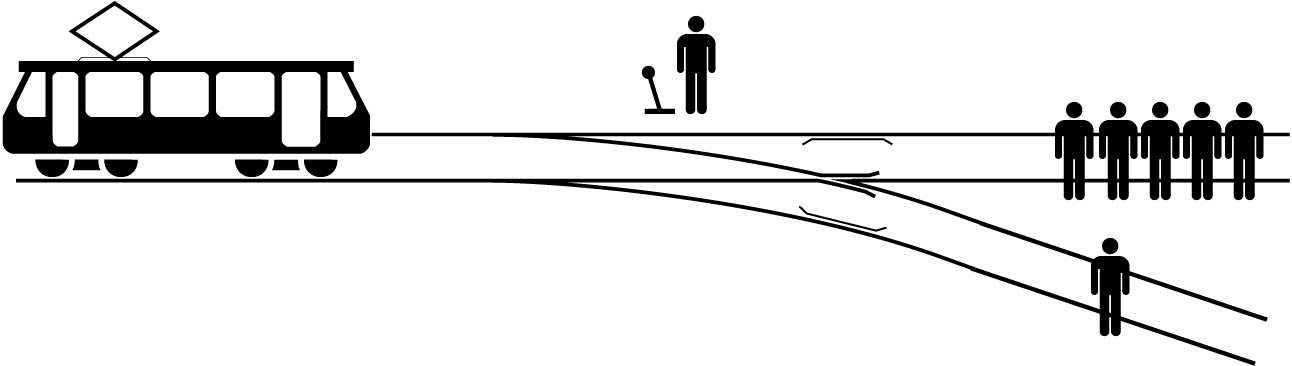

Figure 2. “One of the dilemmas included in the trolley problem: should you pull the lever to divert the runaway trolley onto the side track?” (McGeddon & Zapyon, 2018)

Some argue that the focus on ‘trolley problem’-style dilemmas is misguided altogether. Human drivers are taught to break without swerving in the case of emergency. This procedure is not recommended merely because it is instinctive and simple, but due to the nature of vehicular physics.

“Put in its simplest form, the problem is that swerving sufficiently to avoid an object that is within a car’s stopping distance is always a wildly risky manoeuvre compared to straight-line braking.” (Davnall, 2019)

The self-driving trolley problem can now be seen as an additional choice between a controlled manoeuvre with known risks, and an uncontrolled manoeuvre with unknown risks.

Need for New Infrastructure

Existing vehicle infrastructure might need to be adapted for self-driving cars. As Othman (2021) states, “the human factor … will not be a concern anymore so the geometric design requirements can be relaxed.” The foremost issue with adapting infrastructure to autonomous vehicles will be the transition period, as we cannot remove all infrastructure for ‘dumb’ cars until the transition to self-driving cars is completed.

Whilst infrastructure such as roads can be streamlined during and especially after the transition period, this may increase maintenance of infrastructure. According to Othman (2021), “the decrease in the wheel wander, because of the lane-keeping system, and the increase in the lane capacity, because of the elimination of the human factor, will bring an accelerated rutting potential and will quickly deteriorate the pavement condition.”

This could therefore drastically increase costs for infrastructure maintenance, which is already lacking for existing unautomated vehicles. During the transition period, it might make sense to restrict self-driving cars to fixed routes and lanes, as this “allows safe operation during the early phases of driverless mobility” (Bonte, 2021).

Bonte (2021) argues that the future of cities could “favour large levels of pedestrianisation with regular traffic moved underground via tunnels and hyperloops”, although this will require a significant investment in infrastructure, which may take many years to implement even after the transition period.

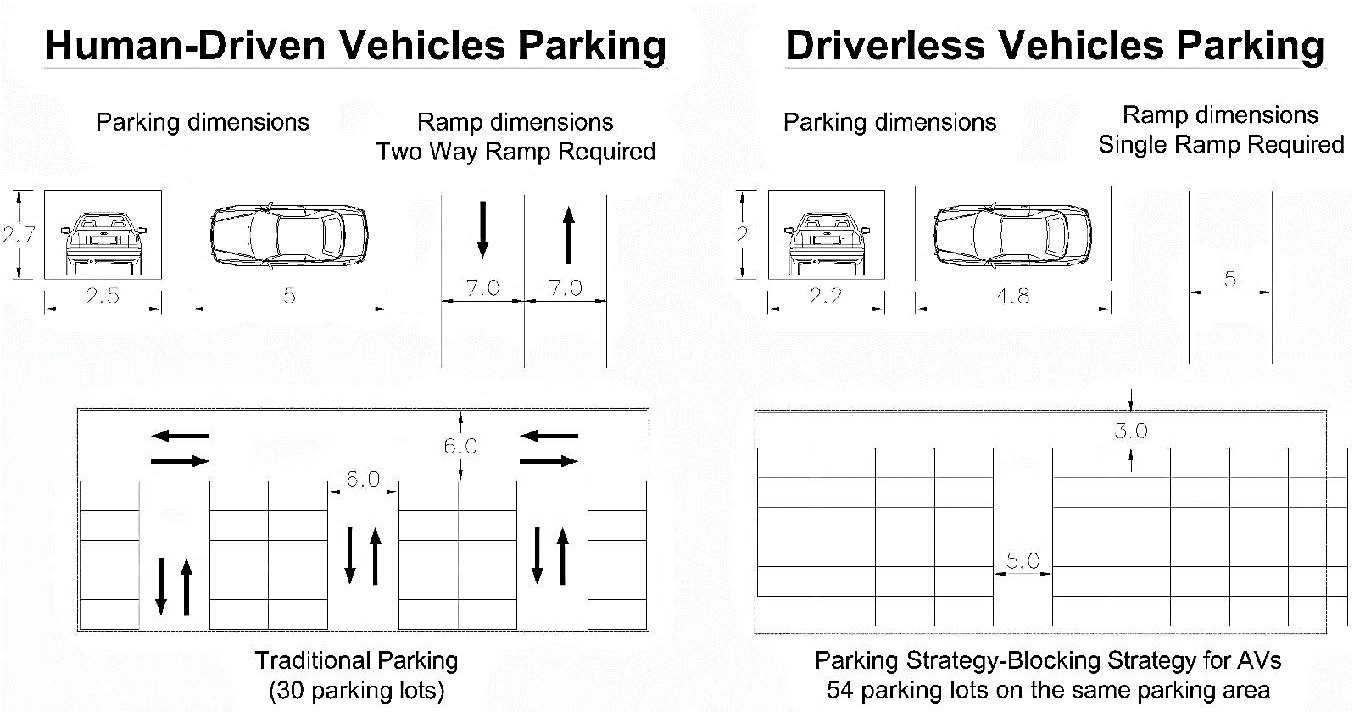

“AVs can significantly reduce the number of the required parking lots … as vehicles will be serving customers at different times [and] the autonomous valet parking system will allow vehicles to park closer to each other” (Otham, 2021). This reduction of parking lots may allow us to free up space for other infrastructure such as roads or even housing.

Figure 3. Parking Strategy for human-driven vehicles and Avs. (left) Conventional parking layout; (right) Autonomous Vehicles parking layout. (Otham, 2021)

Despite the possible advantages, self-driving cars might have a negative impact on traffic congestion, “because AVs will motivate people to make longer trips, travel further, and make additional trips” (Otham, 2021). Autonomous vehicles therefore will possibly bring disadvantages as well as advantages.

Need for a New Legal Framework

Current legal framework is not suitable for handling liability in the event of an accident involving a truly autonomous vehicle. Currently, all self-driving cars on the road have a ‘steward’ or ‘safety-driver’ behind the wheel that can take control if things go wrong and is ultimately responsible for the vehicle’s safe passage. This is a temporary ‘band aid’ solution that eventually needs addressing.

Whilst it is conceivable that in the future, the AI that drive vehicles will be agents, with legal rights and responsibilities, this does not represent the immediate reality of self-driving vehicles.

With the user giving up control of the vehicle, they have also given up their responsibility for its safe use (Gurney, 2017). This stance is of absolute necessity to the adoption of AVs, as no consumer wants to purchase the ‘Car of Damocles’.

Public Acceptance

Having the technology of self-driving cars up to a good standard is insufficient by itself, as the public’s trust is equally important. When a technology is quite recent and seemingly beyond our control, we are naturally more risk-averse towards it.

In a study by Sivak and Schoettle (2015) on the public opinion of self-driving cars, most respondents expressed high levels of concerns about riding in a self-driving car. This is due to the fear/risk of safety issues, malfunction, or system failure. There were also concerns about self-driving cars not performing as well as human drivers.

Last year, 378 people were killed on New Zealand’s roads. This, however, is not the number to beat for autonomous vehicle engineers, as polling suggests that the public acceptance of AVs would require this number to be lowered by a factor of 10.

This risk aversion poses a risk in and of itself, as an excessively cautious approach resulting from high-profile accidents could potentially hinder the acceptance and development of self-driving cars. Such a hinderance could prevent millions from avoiding life-changing injury or even death.